Translated by E. Madison Shimoda

Translated by E. Madison Shimoda

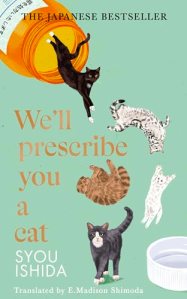

Until now I seem to have avoided the current trend for Japanese novels with cute cat pictures on the cover. It wasn’t a deliberate decision to avoid them – that sort of book just doesn’t usually appeal to me. When I was looking for ideas for cat-related books to read for this year’s Reading the Meow, though, I thought this one sounded intriguing.

We’ll Prescribe You a Cat begins with Shuta Kagawa visiting the Nakagyō Kokoro Clinic for the Soul in Kyoto. Shuta’s unhappiness at work is causing him to suffer from stress and insomnia and he has decided to consult a psychiatrist. However, he quickly discovers that this is no ordinary clinic – first, it proves extremely difficult to find, hidden away down a narrow alleyway; then, instead of prescribing medication, Dr Nikké says something completely unexpected: “We’ll prescribe you a cat”. And with that, Shuta becomes the temporary owner of Bee, an eight-year-old female mixed breed – but will he manage to complete the course of ‘medication’ without any side effects and what will happen when it’s time to give the cat back?

Shuta’s story is the first of five that make up this novel, each one following a similar format with a character entering the Kokoro Clinic and, regardless of their symptoms, being prescribed a cat. The cat is a different one each time, each with his or her own personality and characteristics. Sometimes the cat is compatible with the client; sometimes it seems to cause more trouble and disruption, but in each case, when the prescription comes to an end, the person finds that their life will never be the same again.

Animal-assisted therapy is a legitimate form of therapy used by charities and mental health groups to treat a range of issues, allowing people to spend time with animals in a controlled environment. That’s what I had assumed this book would be about, so I was surprised to see Dr Nikké and his nurse, Chitose, simply handing the clients a cat in a carrier with some food and written instructions – no checks done to make sure the person had a suitable home for the cat, no questions asked about allergies or the needs of other family members. Then, at the end of the week or two week period, the cat is going to be handed back to the clinic and passed on to the next person. It seemed cruel and irresponsible. However, I quickly discovered that the book has a fantasy element – which grows stronger and more bizarre as it progresses – and I was probably taking things too seriously!

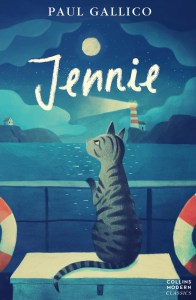

You may be wondering what the fantasy element is. Well, to begin with, the clinic itself is very unusual – sometimes it can be found and sometimes it can’t, depending on the person looking for it and how desperately they need to find it. There’s also something strange about Dr Nikké and Chitose, but I’m not going to say any more about that except that each of the five stories adds a little bit to our understanding of what is going on. Still, when I finished the book I felt that a lot of things were left unexplained or only partly answered. There’s a sequel, We’ll Prescribe You Another Cat, which will be available in English in September, but I’m not sure whether it will provide any more clarity or if it’s just another collection of similar stories. I don’t think I liked this one enough to want to read the sequel, but I did find it interesting and I enjoyed taking part in this year’s Reading the Meow with this book and Paul Gallico’s Jennie!

You may be wondering what the fantasy element is. Well, to begin with, the clinic itself is very unusual – sometimes it can be found and sometimes it can’t, depending on the person looking for it and how desperately they need to find it. There’s also something strange about Dr Nikké and Chitose, but I’m not going to say any more about that except that each of the five stories adds a little bit to our understanding of what is going on. Still, when I finished the book I felt that a lot of things were left unexplained or only partly answered. There’s a sequel, We’ll Prescribe You Another Cat, which will be available in English in September, but I’m not sure whether it will provide any more clarity or if it’s just another collection of similar stories. I don’t think I liked this one enough to want to read the sequel, but I did find it interesting and I enjoyed taking part in this year’s Reading the Meow with this book and Paul Gallico’s Jennie!