After enjoying Emilia Hart’s first novel, Weyward, in 2023, I’ve been looking forward to reading her new one, The Sirens. Weyward linked the stories of three women in different time periods through a family connection, a shared love of nature and a theme of witchcraft. The Sirens also has multiple timelines, but this time the characters are linked by water and the sea.

After enjoying Emilia Hart’s first novel, Weyward, in 2023, I’ve been looking forward to reading her new one, The Sirens. Weyward linked the stories of three women in different time periods through a family connection, a shared love of nature and a theme of witchcraft. The Sirens also has multiple timelines, but this time the characters are linked by water and the sea.

The novel begins in Australia in 2019 with student Lucy waking up from a sleepwalking episode with her hands around her ex-boyfriend’s neck. Ben is not entirely innocent – they broke up after he shared a nude photo of her with his friends – but she’s afraid he’ll report her for assault, so she packs her things and flees. Planning to take refuge with her sister Jess, an artist, Lucy heads for the town of Comber Bay, but on arrival she finds her sister’s house empty, as if it had been abandoned in a hurry. Lucy is concerned, but on learning that Jess did tell one of the neighbours that she would be going away for a while, she decides to wait in the house until she returns.

Comber Bay is a small town on the coast of New South Wales and has a sinister reputation; over a forty year period, eight men disappeared without trace, never to be seen again. Also, in 1982, a baby was found abandoned in a cave not far from Jess’s house. As she waits to hear from her sister, Lucy begins to uncover the truth behind these mysteries – but she becomes distracted by unsettling dreams of another pair of sisters who lived two centuries earlier.

Lucy’s present day story alternates with the story of those other two sisters, Mary and Eliza, who were found guilty of a crime in Ireland in 1800 and transported to Australia on a convict ship. Later in the book, Jess’s story also begins to unfold, mainly in the form of diary entries from the 1990s (the diary reads more like a novel, but I think we just have to suspend disbelief there). It takes a while for all of these threads to come together, but we eventually begin to see how cleverly they are connected. There are some surprising twists that I didn’t see coming, as well as some that I was able to guess before they were revealed. As ever, when a book has more than one timeline, I find that some are more compelling than others – and in this case, I particularly enjoyed Lucy’s story and the flashbacks to Jess’s teenage years. Mary and Eliza never fully came to life for me, so their adventures on board the Naiad didn’t interest me quite as much as I would have liked.

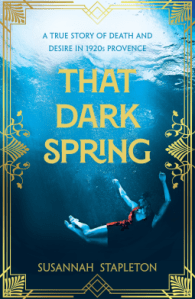

The title and cover of the book made me think there would be more siren/mermaid mythology incorporated into the story, but there’s only a little bit of that. There’s a lot of beautiful watery imagery, though, and water plays a big part in the novel in so many different ways. There’s Mary and Eliza’s sea voyage on the Naiad; the setting of Comber Bay, with its coastline, cliffs and caves; Jess’s paintings of ships; even the rare skin condition Lucy suffers from, aquagenic urticaria. It’s a book with lots of layers and things to think about. Having read two Emilia Hart books now, however, I do have a problem with her portrayal of men. Almost every male character in both books, with only a few exceptions, is either violent and abusive, a rapist or generally misogynistic or predatory. Obviously that’s true of some men, but I think it’s unrealistic that nearly every man who crosses paths with our female protagonists would be a terrible person. I think it should be possible to promote feminism and give women a voice without going too far in the other direction.

Apart from that, I did like the book and loved the eerie atmosphere Hart creates with Lucy alone in the abandoned Cliff House, uncovering the troubled history of Comber Bay’s past while being haunted by the cries of the women on the convict ship. It’s very similar to Weyward in some ways, but also different enough to be an interesting novel in its own right.

Thanks to The Borough Press for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.