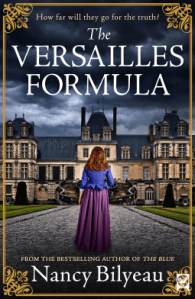

Having loved Nancy Bilyeau’s The Blue and The Fugitive Colours, I was excited to read the new book in the Genevieve Planché series. The Versailles Formula is published this week by Joffe Books and I’m pleased to say that I found it as good as the first two. If you’re new to the series, I would recommend reading the books in order if you can, but there’s enough background information in this one to allow you to start here if you wanted to.

Having loved Nancy Bilyeau’s The Blue and The Fugitive Colours, I was excited to read the new book in the Genevieve Planché series. The Versailles Formula is published this week by Joffe Books and I’m pleased to say that I found it as good as the first two. If you’re new to the series, I would recommend reading the books in order if you can, but there’s enough background information in this one to allow you to start here if you wanted to.

The Versailles Formula is set in 1766 and, like the other books, is narrated by Genevieve Planché, a Huguenot woman who grew up in London after her family left France due to religious persecution. She’s also an aspiring artist who is finding it frustratingly difficult to be taken seriously in a field still dominated by men. As the novel opens, Genevieve is teaching watercolours to a group of young ladies while her husband, the chemist Thomas Sturbridge, is away from home working on a new research project with a scientist friend. Several years earlier Thomas had created a formula for a beautiful new shade of blue – an invention that powerful people in both France and Britain would stop at nothing to obtain. The race for the blue led to murder and treason before an agreement was finally reached that both sides would stop attempting to develop the colour.

Genevieve’s painting lesson is interrupted by the arrival of Under-Secretary of State Sir Humphrey Willoughby, husband of her friend, Evelyn. Sir Humphrey’s appearance sets in motion a chain of events that lead Genevieve to Strawberry Hill, home of the author Horace Walpole. Here she and Sir Humphrey make the shocking discovery that someone has begun producing the blue once more. Have the French broken the treaty they agreed to or is this someone acting alone? How did the blue find its way into Walpole’s home? Accompanied by an army officer, Captain Howard, Genevieve travels to Paris in search of answers.

This book definitely lived up to my expectations and was worth the three year wait since the last one! It was good to catch up with Genevieve again and although I would have liked to have seen more of other recurring characters such as Thomas Sturbridge, there’s a wonderful new character to get to know in the form of Captain Howard. Genevieve is wary of Howard at first, disliking him on sight and unsure as to why Sir Humphrey is entrusting him with such an important mission, but her opinion gradually begins to change and I loved watching their relationship develop as they travel across France.

Although many of the characters in the novel are fictional, there are also some who are real historical figures, most notably Horace Walpole, author of The Castle of Otranto. I particularly enjoyed the section of the book where Genevieve visits Strawberry Hill, his Gothic-style mansion in Twickenham and experiences its ‘gloomth’ – a term coined by Walpole himself to describe his home’s atmosphere of gloom and warmth.

The book is well paced, with tension building as Genevieve begins to wonder exactly who can and can’t be trusted – and whether anyone will see through the false identity she has adopted for her return to France. I thoroughly enjoyed this book, but I did feel that some things were left unresolved at the end, so I hope that means there could be a fourth Genevieve Planché book to look forward to. If so, I’ll certainly be reading it.

Thanks to Joffe Books for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.