Folk horror is not a subgenre I’ve ever really taken the time to explore, so I wasn’t sure what to expect from this new anthology selected and illustrated by the artist Richard Wells. What I found was a collection of sixteen stories, most of them from the 19th and early 20th centuries, all blending folklore with elements of the supernatural and lonely rural settings. Each story is accompanied by a beautiful lino print illustration by Wells which I’m sure will look even more impressive in the physical edition of the book than in the ebook version I read.

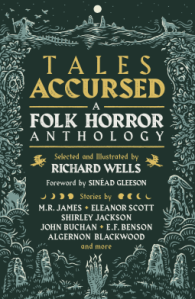

Folk horror is not a subgenre I’ve ever really taken the time to explore, so I wasn’t sure what to expect from this new anthology selected and illustrated by the artist Richard Wells. What I found was a collection of sixteen stories, most of them from the 19th and early 20th centuries, all blending folklore with elements of the supernatural and lonely rural settings. Each story is accompanied by a beautiful lino print illustration by Wells which I’m sure will look even more impressive in the physical edition of the book than in the ebook version I read.

The stories are arranged chronologically, beginning with Sheridan Le Fanu’s The White Cat of Drumgunniol from 1870 and ending with Shirley Jackson’s The Man in the Woods, published posthumously in 2014. I had read both of these authors before (although not these particular stories) and there were two other authors I’d also read previously – John Buchan and E.F. Benson – but the others were all new to me. In fact, there were several I’d never even heard of until now, so it was good to be made aware of them and to be able to try their work for the first time.

As with most anthologies, the stories vary in quality. However, I found that there wasn’t much variety in terms of plot or setting. Many of them, particularly the older ones, are based on Celtic folklore and have similar structures, with our narrator travelling in an unfamiliar part of the countryside and meeting someone who tells them a story about strange sightings or occurrences, which the narrator then experiences for themselves. Although this did make the collection as a whole feel slightly formulaic and repetitive, there were still some stories that were different and stood out. One of these is Woe Water by H.R. Wakefield, which unfolds in the form of diary entries written by a man with a troubled past who moves into a remote lakeside cabin and begins to struggle with his conscience. I also enjoyed Elinor Mordaunt’s The Country-Side, told from the perspective of a parson’s wife whose relationship with her unfaithful husband takes a sinister turn when she meets an old woman in the village who is said to be a witch.

Ancient Lights by Algernon Blackwood is another highlight – it has a wonderfully eerie atmosphere as the narrator describes his journey through enchanted ancient woodland. The Shirley Jackson story, The Man in the Woods, in which a man accompanied by a stray cat stumbles upon an old house inhabited by three strange people, is also very good. It’s packed with references to mythology and witchcraft and there are lots of layers to unravel, but the open ending left me frustrated and wanting to know more!

Despite the ‘folk horror’ label in the title, I found the stories in this collection creepy or unsettling rather than frightening. I deliberately haven’t said much about any of the individual stories because some of them are very short and it would be easy to spoil them, but overall I did enjoy the book and am interested in reading more by some of these authors.

Thanks to Unbound for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.

I’m counting this as my second book towards this year’s RIP challenge.

I’m counting this as my second book towards this year’s RIP challenge.