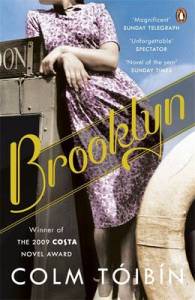

Brooklyn tells the story of Eilis Lacey, a young woman who lives in a small town in Ireland with her mother and sister. It’s the 1950s, only a few years after the end of World War II and it’s not easy to find a good job in a town like Enniscorthy. When Eilis is offered the chance to work and study in New York she leaves her family behind and prepares to start a new life in Brooklyn. After a traumatic journey across the Atlantic, we see how she settles into her new home and job, struggles with homesickness and makes new friends. But it’s during a trip home to Ireland that Eilis is faced with making the biggest decision of her life…

Brooklyn tells the story of Eilis Lacey, a young woman who lives in a small town in Ireland with her mother and sister. It’s the 1950s, only a few years after the end of World War II and it’s not easy to find a good job in a town like Enniscorthy. When Eilis is offered the chance to work and study in New York she leaves her family behind and prepares to start a new life in Brooklyn. After a traumatic journey across the Atlantic, we see how she settles into her new home and job, struggles with homesickness and makes new friends. But it’s during a trip home to Ireland that Eilis is faced with making the biggest decision of her life…

Brooklyn is a warm, gentle story with an old-fashioned charm. It’s not the most original book I’ve ever read and it’s not the most exciting or dramatic, but when I picked it up and started reading, I found it was just what I was in the mood for. Tóibín tells his story using simple language and a controlled, understated writing style and it was actually quite refreshing to read a book with such clear, direct prose and such a straightforward plot. The book was published in 2009 (and made the Booker Prize long list that year) but if I hadn’t been aware of that I could almost have believed it was written in Eilis’s own era because it does somehow have a very 1950s feel.

Eilis herself is a pleasant, likeable person. Looking at other reviews, many people have complained that she is too passive, allowing other people to run her life for her. I could accept her passivity as part of her quiet, innocent personality, though I agree that it didn’t make her a particularly strong or memorable character. I thought some of the minor characters were more interesting to read about – such as Georgina, the woman who befriends Eilis on her nightmare ocean crossing, or Miss Kelly, who runs the local shop in Enniscorthy where Eilis used to work. We stay with Eilis’s perspective throughout the whole book which means we only get to see the other characters when they are interacting with her directly, but something Tóibín does very successfully is to explore the relationships between Eilis and the important people in her life.

The book does touch on some of the social issues of the time – we learn a little bit about Ireland’s economy, the Holocaust is briefly mentioned, and we get a glimpse of racism in 1950s New York when Eilis starts serving black customers at Bartocci’s department store. But although those issues and others are there in the background they don’t form a major part of the plot. Instead, the focus of Brooklyn is very much on Eilis and the things that affect her personally: her new job at Bartocci’s, studying bookkeeping at evening classes, making new friends and visiting her boyfriend. The reader is immersed completely in the small details of Eilis’s daily life, something which could easily have become very boring, but in Tóibín’s hands is fascinating and compelling.

I haven’t personally had the experience of living in another country and I’m not sure how I would feel about it, but there were still parts of Eilis’ story that resonated with me and that I could identify with. I loved Brooklyn – and I was happy with the way the book ended too!