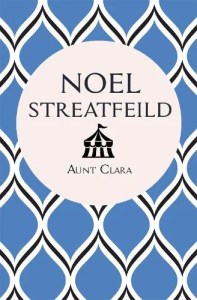

My final book for the 1952 Club being hosted this week by Simon and Karen is one of Noel Streatfeild’s adult novels. I loved Streatfeild as a child but came to her books for adults just a few years ago. So far I’ve enjoyed The Winter is Past and Caroline England and hoped that her 1952 novel, Aunt Clara, would be another good one.

My final book for the 1952 Club being hosted this week by Simon and Karen is one of Noel Streatfeild’s adult novels. I loved Streatfeild as a child but came to her books for adults just a few years ago. So far I’ve enjoyed The Winter is Past and Caroline England and hoped that her 1952 novel, Aunt Clara, would be another good one.

Before we meet the title character, Streatfeild introduces us to Simon Hilton, a wealthy, curmudgeonly man approaching his eightieth birthday, who lives in London with his valet, Henry. Simon has never married, but has five nieces and nephews, most of whom now have children and grandchildren of their own. None of them care much for Simon – and the feeling is mutual – but they all have their eyes on his money and don’t want to risk being disinherited. The old man is looking forward to celebrating his birthday in August and when he receives a stream of letters from various family members suggesting that he switch his party to July instead as it would be more convenient for them, Simon is furious. Feeling disrespected and insulted, he decides to teach them all a lesson!

A few weeks after his birthday party (which was held in August, despite his family’s complaints), Simon dies and everyone gathers for the reading of the will. To their shock and disgust, they hear that everything has been left to Clara, Simon’s sixty-two-year-old niece. Clara is one of the only people in the family who is not greedy and selfish: she looked after her parents until their deaths, sacrificing her own chance of marriage in the process; she is always ready to help her siblings and their children whenever they call on her; she carries out work for charity and sees only the best in everyone else. It may seem that Simon has rewarded her for her goodness, but the bequests include some odd things to leave to a religious, teetotal spinster in her sixties – a small brothel, The Goat in Gaiters pub, Simon’s racehorses and racing greyhounds, a fairground game called Gamblers’ Luck, and two children from a circus. Is Simon playing one last cruel joke from beyond the grave?

I enjoyed Aunt Clara, although I felt that the plot jumped around too much in the second half of the book, making it a bit difficult to follow, particularly as there are so many characters to keep track of as well. It’s fascinating to see how Clara deals with her unusual inheritance, though; she’s endearingly naive and innocent, oblivious to Simon’s malicious humour, and considers each of his bequests to be a ‘sacred trust’. Her efforts to care for each of the people or things entrusted to her eventually begin to give her a different perspective on life and on things she’s always viewed as sins, such as drinking and gambling. She also has to contend with the rest of the Hilton family, who switch their attentions to her, hoping to get their hands on some of her newly gained wealth!

As I’ve mentioned, there are far too many characters – and only a few of the family members are drawn with any depth. One character who does jump out of the pages, though, is Henry, Simon’s manservant, a no-nonsense Cockney who sees the goodness in Clara and takes her under his wing. Henry is present throughout the book and speaks in dialect, including a lot of rhyming slang, which I found a bit tiring to read after a while. Aunt Clara isn’t my favourite of the Streatfeild novels I’ve read so far, then, but I think there’s a lot more to like than to dislike. I was interested to find that it was made into a film starring Margaret Rutherford in 1954. Has anyone seen it?

As I’ve mentioned, there are far too many characters – and only a few of the family members are drawn with any depth. One character who does jump out of the pages, though, is Henry, Simon’s manservant, a no-nonsense Cockney who sees the goodness in Clara and takes her under his wing. Henry is present throughout the book and speaks in dialect, including a lot of rhyming slang, which I found a bit tiring to read after a while. Aunt Clara isn’t my favourite of the Streatfeild novels I’ve read so far, then, but I think there’s a lot more to like than to dislike. I was interested to find that it was made into a film starring Margaret Rutherford in 1954. Has anyone seen it?