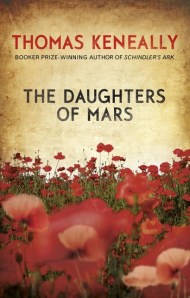

Until I picked up The Daughters of Mars in the library I was only really aware of Thomas Keneally as the author of Schindler’s Ark (which I haven’t read), the book on which the film Schindler’s List was based. I was surprised to find that he has written more than forty other books (both fiction and non-fiction) and I’m pleased that I’ve finally read one. The Daughters of Mars is the story of two Australian sisters, Naomi and Sally Durance, who serve as nurses with the Australian Army Nursing Service during the First World War. I had a few problems with the book, mainly due to the unusual writing style, but it gave me lots of fascinating insights into the challenges facing wartime nurses.

Until I picked up The Daughters of Mars in the library I was only really aware of Thomas Keneally as the author of Schindler’s Ark (which I haven’t read), the book on which the film Schindler’s List was based. I was surprised to find that he has written more than forty other books (both fiction and non-fiction) and I’m pleased that I’ve finally read one. The Daughters of Mars is the story of two Australian sisters, Naomi and Sally Durance, who serve as nurses with the Australian Army Nursing Service during the First World War. I had a few problems with the book, mainly due to the unusual writing style, but it gave me lots of fascinating insights into the challenges facing wartime nurses.

When we first meet the Durance sisters, they are leading very different lives: Naomi has left home and has gone to work at a hospital in Sydney, while Sally has remained on the family dairy farm in the Macleay Valley and is caring for their sick mother. The two girls have little in common other than a love of nursing but an unwelcome bond is formed between them when their mother dies under tragic circumstances. Deciding to get away for a while from Australia and the memories it holds, they enlist on the hospital ship Archimedes. Sailing first to Egypt and then to the Dardanelles, the sisters are kept busy treating casualties of the Gallipoli Campaign and as the war progresses, they find themselves in separate hospitals on the Western Front where they face the horrors of trench warfare and gas attacks.

The work is demanding, dangerous and emotionally draining, but also very rewarding. As well as learning new skills, both girls find new friends among the other young nurses and meet the men they hope to spend the rest of their lives with. Of course, nothing is certain in times of war and there’s no guarantee that either they or the men they love will survive long enough for marriage to become a possibility. And the most important relationship of all – the one between Naomi and Sally – will remain tense and strained until the sisters can find a way to put the past behind them.

I can’t say that I particularly enjoyed reading The Daughters of Mars, but I did find it interesting to learn about the work of the Australian nurses, which is something I haven’t read about before. Most of what we hear about the Great War involves stories of men fighting on the front lines, but it’s important to remember the important contribution of these brave women who also played their part in helping the war effort. While I have read British author Vera Brittain’s first-hand account of life as a wartime nurse, Testament of Youth (which I highly recommend), this is the first time I’ve read about the same subject from an Australian perspective. It was fascinating, although if you’re squeamish I should warn you that Sally and Naomi are faced with all kinds of gruesome battle wounds, injuries and illnesses – and they are described in a lot of detail, along with the medical procedures and surgical operations that are used to treat them.

Now I need to explain what I didn’t like about this book and it’s something that’s really a matter of personal taste. In his author’s note, Keneally tells us that if the use of punctuation in the novel sometimes seems unusual it’s because he has taken inspiration from ‘the forgotten private journals of the Great War, written by men and women who frequently favoured dashes rather than commas’. The dashes didn’t bother me, but the lack of quotation marks did! We use punctuation to indicate speech for a reason and because it wasn’t there I found that the text didn’t flow properly, which made it unnecessarily difficult to read. I felt that I was viewing the events of the story from a distance and never fully engaged with either Durance sister. In fact, I found most of the characters quite bland and difficult to tell apart. There was none of the passion and emotion that I would have expected from a book like this.

I can’t comment on the accuracy of the book (as I said, wartime nursing is not a subject I know much about) but it does seem to have been very well researched and covers almost every aspect of the war you can think of from conscription and conscientious objectors to shell shock and the Spanish flu. Despite the problems I had with Keneally’s writing, I found the story interesting enough to keep reading until I reached the end. And what an intriguing ending it was! Unfortunately I can’t tell you what was so special about it, but it was completely unexpected and I’m still not sure whether I liked it or not – it’s the sort of ending that will leave you wondering why the author chose to end the book in that way and what message he wanted us to take from it.

If anyone has read any other Thomas Keneally books, let me know if you think I should try another one. Are his other books written in a more conventional style?