I’m ashamed to say I had never come across this classic American children’s novel until Constance of Staircase Wit recommended it when I commented on one of her reviews that I would like to read more about life on New York’s Lower East Side. Constance kindly sent me a copy, which I have now read and enjoyed!

I’m ashamed to say I had never come across this classic American children’s novel until Constance of Staircase Wit recommended it when I commented on one of her reviews that I would like to read more about life on New York’s Lower East Side. Constance kindly sent me a copy, which I have now read and enjoyed!

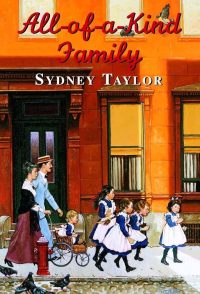

First published in 1951, the book follows five young sisters through a year of their childhood in 1912. Ella, at twelve, is the oldest and four-year-old Gertie is the youngest, with Henny (Henrietta), Sarah and Charlotte in between. They are known as an ‘all-of-a-kind family’ due to being all girls – or, as the librarian refers to them, a ‘step-and-stairs family’ because of their evenly spaced ages. They live in an apartment on the Lower East Side and Papa runs a junk shop nearby while Mama looks after the children and their home.

In the first chapter, Sarah is upset because a friend has borrowed her library book and lost it. She’s sure she’ll be in big trouble and banned from going to the library ever again. However, the librarian, Miss Allen, is sympathetic and, knowing that the family would be offended by charity, she agrees to let Sarah pay for the book one penny a week. Miss Allen becomes a good friend to the girls after this and we meet her again later in the book, but meanwhile there are lots of other adventures to be had – including making a fun game from dusting the apartment, going to the market with Mama, and getting lost at Coney Island.

This is such a charming book, I’m sure I would have loved it as a child. The five girls are all very endearing and Taylor gives them all individual personalities of their own. Ella, being nearly a teenager, is the most mature of the sisters and is beginning to form romantic attachments; ten-year-old Henny is independent and rebellious, while Sarah is more studious. The two youngest girls are less well developed, but Gertie, the baby of the family, looks up to Charlotte who is two years older and they have a particularly close relationship.

One of the most interesting things about this book is that the girls belong to a Jewish family, so we are given lots of descriptions of them preparing for Jewish holidays such as Purim and Passover (as well as celebrating the Fourth of July) – and because the girls are so young, Mama and Papa explain to them the meanings of each custom and tradition, which can be very helpful for non-Jewish readers! Not many of the books I remember reading as a child featured children who were anything other than Christian, so it’s good to know that this book existed even if I wasn’t aware of it.

This is a lovely book (and also the first in a series). Thanks to Constance for introducing me to it.