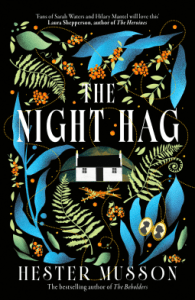

Have you ever suffered from sleep paralysis – the feeling that you’re awake but can’t move your body? Maybe it’s accompanied by a sensation of pressure on your chest, as if something is pinning you to the bed, or the impression that someone is in your room. It’s more common than you may think – many people will experience it at least once or twice in their life – and it inspired the famous painting, The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli. In fact, the word ‘nightmare’ itself (originally hyphenated as night-mare) comes from the idea of a mythological female demon (a ‘mare’ or ‘hag’) sitting on the chest of a sleeping person. Someone who has had a lot of experience of these terrifying night-mares is Lil Vincent in Hester Musson’s new novel, The Night Hag.

Have you ever suffered from sleep paralysis – the feeling that you’re awake but can’t move your body? Maybe it’s accompanied by a sensation of pressure on your chest, as if something is pinning you to the bed, or the impression that someone is in your room. It’s more common than you may think – many people will experience it at least once or twice in their life – and it inspired the famous painting, The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli. In fact, the word ‘nightmare’ itself (originally hyphenated as night-mare) comes from the idea of a mythological female demon (a ‘mare’ or ‘hag’) sitting on the chest of a sleeping person. Someone who has had a lot of experience of these terrifying night-mares is Lil Vincent in Hester Musson’s new novel, The Night Hag.

It’s 1886 and Lil Vincent has been free of the night-mares, as she calls them, for many years, but recently they have started again and are becoming increasingly intense. Frightened and desperate, Lil writes a letter to the renowned Edinburgh doctor, Dr Lachlan. Relieved to be able to open her heart to somebody at last, even somebody she’s never met, she finds herself telling him all about her childhood, growing up as the daughter of a medium who forced her to participate in fraudulent séances.

Her childhood has left scars that still persist, even today as she tries to build a new life for herself as an archaeologist. Lil is assisting Nils and Effie Jensen with a dig on what they believe is a Bronze Age burial mound in the fictional Scottish village of Pitcarden. When they come across two cinerary urns and a bronze knife, Lil thinks they are on the verge of a significant discovery, but it seems that the villagers are unhappy with their presence and they may not be allowed to complete their excavations.

This is the second novel I’ve read by Hester Musson, the first being The Beholders. Although I found this one a more original and intriguing story, I did have some of the same problems I had with the other book – mainly that the first half is very slow and it took me a long time to become immersed in it. It didn’t help that there are several different threads to the story – Lil’s sleep disturbances, the séances and the archaeological dig – and they all feel very separate, never really coming together until the end.

Once I did get into the story, I found it interesting. There’s a good sense of time and place, with the community of rural Pitcarden steeped in superstition and folklore. The second half of the book drew me in much more than the first half did, and I began to have a lot of sympathy for Lil as she discovers that almost everyone in her life has been lying to her or deceiving her in one way or another. The way one particular character betrays her trust is quite shocking and Lil is deeply affected by it all. But although it’s a dark book, there are some glimmers of hope in the final chapters and the ending is satisfying, so I’m glad I persevered with it.

If you read this book and enjoy it, I would also recommend reading The Hill in the Dark Grove by Liam Higginson, another book about archaeology and superstition in a rural setting. It has a similar tone and atmosphere and I think it may appeal to the same readers.

Thanks to 4th Estate and William Collins for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.