This month Karen of Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings is hosting #ReadIndies, celebrating books from independent publishers. I’ve never read anything published by Fitzcarraldo Editions before, so this seemed a good opportunity to read one of their books.

This month Karen of Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings is hosting #ReadIndies, celebrating books from independent publishers. I’ve never read anything published by Fitzcarraldo Editions before, so this seemed a good opportunity to read one of their books.

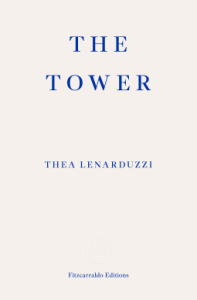

The Tower is a difficult book to describe. It’s not quite fiction, but it doesn’t feel like non-fiction either. It’s a memoir but it’s also an essay and an ode to the power of storytelling. The book follows an author known only as ‘T.’ – presumably Thea Lenarduzzi herself – as she becomes obsessed with the story of a young woman, Annie, who developed tuberculosis in the early 20th century and, according to local legend, was locked away by her father in a tower specially built on the family estate. After living there in isolation for several years, she is said to have died from the disease and although the house has since been demolished, the tower still remains.

T. becomes completely fixated on Annie and her tragic life, determined to find out everything she can about her illness, her imprisonment and her death. She spends a lot of time researching the history of TB, its symptoms and the various treatments, also looking at the lives of famous sufferers such as the author Katherine Mansfield. She visits the now abandoned tower, speaks to historians and archivists and listens to tales told by local residents. All of this is covered in the first two sections of the book and I found most of it fascinating. T. goes off on a lot of lengthy tangents and meanders from one subject to another, but in general Annie’s story was very compelling…

Until, suddenly, we discover that everything we – and T. – thought we knew about Annie may not necessarily be completely accurate after all. In the third section of the book, Lenarduzzi switches from writing in the third person to the first person and becomes herself again, instead of a character known as T. This final section takes the form of a long discussion of storytelling, raising lots of intriguing questions. What is a story and who chooses how it should be told? What is it that draws us to certain stories and not others? As Lenarduzzi explains:

Perhaps for now I should simply say that we don’t always tell the story we want to tell. We can’t always choose our place in it, nor how it ends, or even if it does. That, reader, is the stuff of fiction.

The Tower, then, wasn’t quite what I expected, but it’s a book that surprised me several times and left me with a lot to think about at the end! Thea Lenarduzzi has written another book, Dandelions, inspired by her family history, which sounds equally interesting.