It’s the first Saturday of the month which means it’s time for another Six Degrees of Separation, hosted by Kate of Books are my Favourite and Best. The idea is that Kate chooses a book to use as a starting point and then we have to link it to six other books of our choice to form a chain. A book doesn’t have to be connected to all of the others on the list – only to the one next to it in the chain.

This month we’re starting with Knife by Salman Rushdie. Here’s what it’s about:

On the morning of 12 August 2022, Salman Rushdie was standing onstage at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York, preparing to give a lecture on the importance of keeping writers safe from harm, when a man in black – black clothes, black mask – rushed down the aisle towards him, wielding a knife. His first thought: So it’s you. Here you are.

What followed was a horrific act of violence that shook the literary world and beyond. Now, for the first time, Rushdie relives the traumatic events of that day and its aftermath, as well as his journey towards physical recovery and the healing that was made possible by the love and support of his wife, Eliza, his family, his army of doctors and physical therapists, and his community of readers worldwide.

I haven’t read Knife, but I’m going to begin my chain by linking to the one book I have read by Salman Rushdie: The Enchantress of Florence (1). This unusual novel takes us to a 16th century India populated with giants and witches, where emperors have imaginary wives and artists hide inside paintings.

I read The Enchantress of Florence for a reading event called A More Diverse Universe hosted by a fellow blogger in 2013. The following year, for the same event, I read another book by an Indian author – The Twentieth Wife by Indu Sundaresan (2). It’s set in 17th century Mughal India and is the first in a trilogy of novels describing the history behind the construction of the Taj Mahal.

From twentieth to tenth now! The Tenth Gift by Jane Johnson (3) is a fictional account of the 1625 raid on Cornwall by Barbary pirates who took sixty men, women and children into captivity to be sold at the slave markets of Morocco. The novel is divided between the past and the modern day, focusing on the story of one of the young women abducted during the raid.

Another author known for her books set in her native Cornwall is Daphne du Maurier. I could have chosen several of her novels for my chain, but I’ve decided on Jamaica Inn (4). This 1936 classic features stormy weather, smugglers, locked rooms, shipwrecks, desolate moors, and a remote, lonely inn – everything you could ask for in a Gothic novel! It isn’t one of my absolute favourites by du Maurier, but I enjoyed it much more on a re-read several years ago.

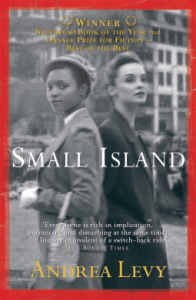

Using Jamaica as my next link, Small Island by Andrea Levy (5) is about a Jamaican couple who leave their island in the 1940s to come to another island, Britain. The book is narrated by the two Jamaican characters and the British couple whose house they lodge in, giving a range of voices and perspectives.

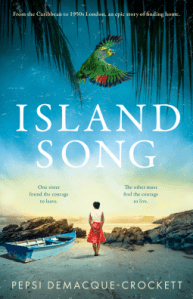

My final book is linked by a word in the title (island) and also a theme of immigration. Island Song by Pepsi Demacque-Crockett (6) follows the stories of two people from St Lucia who start new lives in London in the 1950s. The book is inspired by the author’s own family history and I enjoyed reading about the experiences of the characters, both good and bad.

~

And that’s my chain for April! The links have included Salman Rushdie books, blogging events, positional numbers, Cornwall, Jamaica and immigration. My chain has taken me from India to St Lucia via Italy, Morocco, England and Jamaica!

Next month we’ll be starting with Rapture by Emily Maguire.