Translated by Elizabeth Portch

Translated by Elizabeth Portch

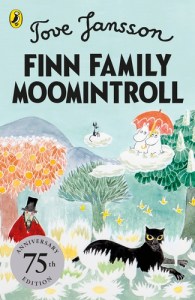

I’ve never read a Moomin book until now – and if it hadn’t been for Mallika of Literary Potpourri and Chris of Calmgrove hosting #Moominweek this week (in time for Paula’s Moomin-themed wedding), I would probably never have picked one up. I’ve seen some of the cartoons/animated series, but it hadn’t occurred to me that I might enjoy reading the books. With no idea where to start – I’ve found several recommended reading orders, which aren’t necessarily chronological – I decided to begin with Finn Family Moomintroll and I think it was a good choice! As it was originally published in Swedish, it also counts towards Women in Translation Month.

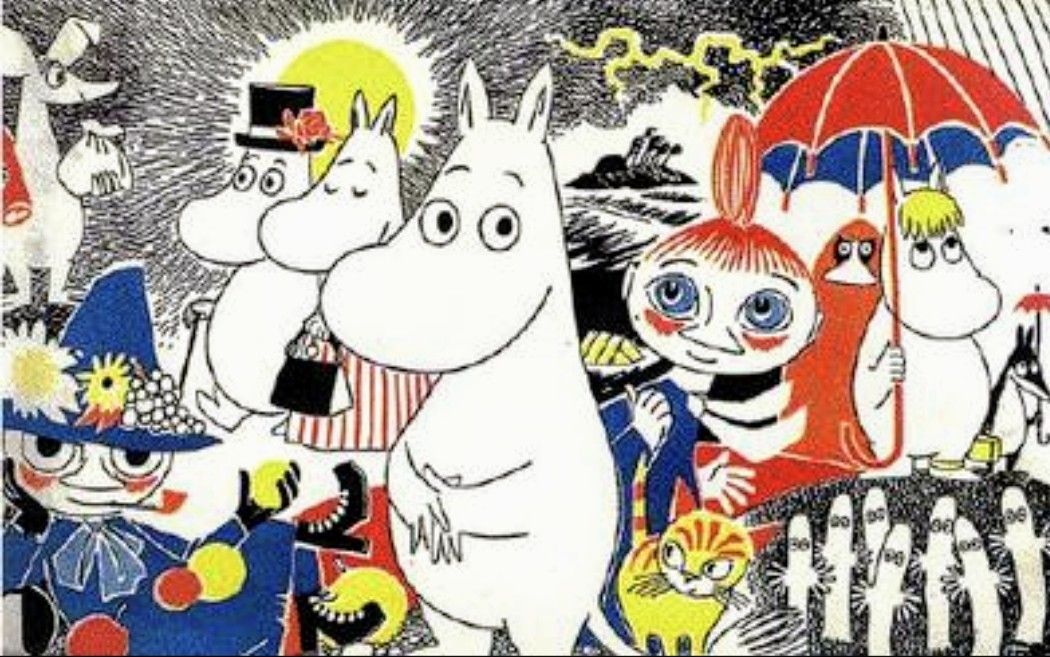

First of all, what are Moomins? Well, they’re small, troll-like creatures who live in Moominvalley. There’s Moomintroll and his parents, Moominmamma and Moominpappa, and an assortment of friends including the Snork and the Snork Maiden (a related species, but with hair), Sniff, a strange little creature resembling a kangaroo who has been adopted by the family, and Snufkin, who wears old clothes and a wide-brimmed hat. You can see some of them, and others, in the illustration below:

Finn Family Moomintroll begins with the Moomin family preparing for their winter hibernation. After waking up again in spring, the book then takes us through the rest of the year, during which the Moomins have a series of adventures revolving around the discovery of a top hat belonging to a Hobgoblin. The hat turns out to have magical powers – some eggshells dropped into it become clouds for the children to ride on, and when Moomintroll himself hides inside it during a game, he too undergoes an unexpected transformation. The Moomins also go on an expedition to the Island of the Hattifatteners, are visited by two tiny creatures called Thingumy and Bob, and finally encounter the Hobgoblin, who has come in search of the missing King’s Ruby.

This book was first published in 1948 (and translated into English in 1950) and is the third in the Moomins series by order of publication. Although it would have been helpful to see how the various characters were first introduced, I didn’t really feel that I’d missed out on much by not reading the previous two books first – and in fact, this one was apparently marketed as the first in the series until the 1980s. I do wonder about the original Swedish title, Trollkarlens hatt, which translates to The Magician’s Hat; he is referred to as a Hobgoblin in the edition I read, but ‘Magician’ would have made more sense, I think.

The book has an episodic feel, with each chapter almost a separate little story in itself, linked by the common thread of the Hobgoblin’s Hat and its magical properties. There’s a focus on the relationships between friends and family members and on the various quirks and eccentricities of the characters. It’s obviously aimed at children, but as with all good children’s books it can be enjoyed by adults as well. I’m not even sure if I would have liked it as a child; I was never a big fan of the adaptations and I think I probably appreciated the book more now than I would have done when I was younger.

The book has an episodic feel, with each chapter almost a separate little story in itself, linked by the common thread of the Hobgoblin’s Hat and its magical properties. There’s a focus on the relationships between friends and family members and on the various quirks and eccentricities of the characters. It’s obviously aimed at children, but as with all good children’s books it can be enjoyed by adults as well. I’m not even sure if I would have liked it as a child; I was never a big fan of the adaptations and I think I probably appreciated the book more now than I would have done when I was younger.

There aren’t really any deep themes here, but there’s a message of kindness and tolerance (the Moomins welcome all sorts of visitors and unusual creatures into the Moominhouse) which would have been more relevant than ever in the aftermath of World War II. I’ve heard that some of the later books in the series have more depth. I’ll probably try another one, although not immediately, and I’m interested in reading Tove Jansson’s adult books as well.