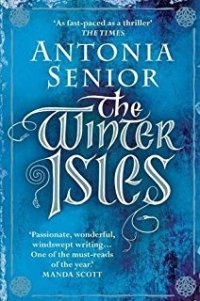

One of the many things I love about reading historical fiction is that it gives me an opportunity to learn about lesser-known historical figures – the ones who were never mentioned in my school history lessons and of whom I could otherwise have gone through the rest of my life in complete ignorance. One of these is Somerled, whose story is told in Antonia Senior’s beautifully written The Winter Isles. Set in 12th century Scotland, we follow Somerled as he sets out to prove himself as a warrior and claim the right to call himself Lord of the Isles.

One of the many things I love about reading historical fiction is that it gives me an opportunity to learn about lesser-known historical figures – the ones who were never mentioned in my school history lessons and of whom I could otherwise have gone through the rest of my life in complete ignorance. One of these is Somerled, whose story is told in Antonia Senior’s beautifully written The Winter Isles. Set in 12th century Scotland, we follow Somerled as he sets out to prove himself as a warrior and claim the right to call himself Lord of the Isles.

We first meet Somerled as a boy in 1122. The son of a minor chieftain from the Western Isles, he is already becoming aware of his father’s weaknesses as a leader – and in this unpredictable, dangerous world, strong leadership is vital. After his father’s hall is burned during a raid, Somerled gets his chance to step forward and take control and, despite his youth, he finds that is able to command the loyalty and respect of his men. But Somerled is an ambitious young man and if he is to achieve his dreams he must build alliances with lords and rulers of neighbouring islands while conquering others – as well as keeping an eye on the movements of Scotland’s king, David, in nearby Alba.

As you can probably tell from what I’ve said so far, The Winter Isles does include quite a lot of battle scenes and descriptions of raids by land and by sea, but there are other layers to the novel too. It isn’t a book packed with non-stop action; there are quiet, reflective sections in which Antonia Senior’s choice of words paint beautiful pictures of the sea and the Scottish islands, their landscapes and their wildlife. She also explores what Somerled is like as a person and how he grows and changes as his power increases.

Not all of the story is told from Somerled’s perspective. There are also chapters narrated by two women, his childhood friend Eimhear (known as ‘the otter’) and the beautiful Ragnhild, both of whom play important but very different roles in Somerled’s life. Eimhear and Ragnhild have strong and distinctive voices and I thought the decision to let them tell their own stories in their own words was a good one, showing what life was like for women during that period and also offering different views of Somerled’s character.

The Winter Isles is a lovely, poignant, intelligent novel which made me think, at times, of King Hereafter by Dorothy Dunnett. However, the comparison is mainly in the setting; the writing style in The Winter Isles is lighter and dreamier and there’s something about it that prevented me from becoming as absorbed in Somerled’s story as I would have liked. This is an impressive book but not one that I particularly loved. Still, I’m now curious about Antonia Senior’s other novels, Treason’s Daughter and The Tyrant’s Shadow, set during the English Civil War and rule of Oliver Cromwell respectively.

As for Somerled, it seems that his portrayal in The Winter Isles is based on a mixture of history, myth and legend; many of the facts regarding the real man have been lost in the mists of time, but the story Antonia Senior has created for Somerled and his children to fill in the gaps feels convincing and realistic. Now that I’ve been introduced to him, I would like to read more. Has anyone read Nigel Tranter’s Lord of the Isles? Are there any other books you can recommend?