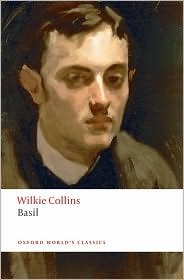

In 19th century literature, a man can approach a girl’s father, ask for permission to marry her and be given that permission, all without the girl having any say in the matter whatsoever. Sometimes the potential husband has only actually spoken to the girl once or twice; sometimes not at all – and they certainly haven’t had time to get to know each other properly. Basil by Wilkie Collins is a good example of why these arrangements were often doomed to failure and caused unhappiness both for the husband and the wife.

Our narrator, the Basil of the title, is the son of a rich gentleman who is proud of his family’s ancient background and despises anyone of a lower social standing. When Basil meets Margaret Sherwin on a London omnibus he falls in love at first sight and becomes determined to marry her. Unfortunately Margaret is the daughter of a linen-draper, the class of person Basil’s father disapproves of most of all, so he decides not to tell his family about her just yet.

Mr Sherwin agrees to Basil marrying Margaret – but he insists that the wedding must take place immediately and that Basil must then keep the marriage secret for a whole year, not even seeing his wife unless Mr or Mrs Sherwin are present. This unusual suggestion should have told Basil that something suspicious was going on but he’s so blinded by love that he doesn’t care – until it’s too late…

Basil was one of Collins’ earliest novels and it shows, as it’s just not as good as his more famous books such as The Woman in White. The story took such a long time to really get started, with Basil introducing us to the members of his family, giving us every tiny detail of their appearance, personality and background. The second half of the book was much more enjoyable, filled with action, suspense and all the elements of a typical sensation novel including death, betrayal and adultery (Victorian readers apparently found the adultery scenes particularly shocking). There are lots of thunderstorms, people fainting and swooning, fights in the street, and everything you would expect from a Victorian melodrama.

All of Collins’ books are filled with strong, memorable characters and this was no exception. There’s Basil’s lively, carefree brother Ralph, his gentle, kind hearted sister Clara, the poor, frail Mrs Sherwin and the sinister Mr Mannion. However, I thought the overall writing style of this book was slightly different to what I’ve been used to in his later books – although I can’t put my finger on exactly what the difference was. This is not a must-read book but if you like the sensation novel genre, you’ll probably enjoy this one.