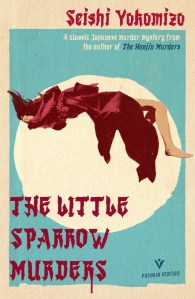

Over the last few years, Pushkin Press have been publishing Seishi Yokomizo’s Kosuke Kindaichi mysteries in new English translations. This is the latest, but I found it different from the previous ones in several ways.

First, where the other books are full-length novels, Murder at the Black Cat Cafe is a novella (this edition also includes another short story, Why Did the Well Wheel Creak?, to make the book more substantial). Yokomizo’s detective, Kosuke Kindaichi, plays a prominent role in the first story, but a very small one in the second – in fact, I wouldn’t really call that one a Kindaichi mystery at all as he only appears right at the end. Both stories belong to the type Yokomizo refers to in the prologue as ‘faceless corpse’ mysteries – in other words, where the murder victim has had their face destroyed so they can’t be identified.

The other main difference is in the setting. Usually the Kindaichi mysteries are set in rural Japan – a small village, a country house, a remote island – but Murder at the Black Cat Cafe has a city setting: Tokyo’s red-light district, an area known as the Pink Labyrinth. First published in 1947, the story takes place just after the war and begins with a policeman on patrol discovering the faceless body of a woman in the garden of the Black Cat Cafe, an establishment owned until very recently by the Itojimas, who have just sold it and moved away. Beside the corpse is the body of a black cat, which has also been killed. It’s assumed that the cat is the famous mascot of the Cafe – until the Cafe’s black cat emerges alive and well. Where did the other cat come from and who is the dead woman?

I enjoyed the post-war urban setting, but with the second story, Why Did the Well Wheel Creak?, we are back on more familiar ground with a family living in a remote village. The patriarch, Daizaburo, has two sons – one legitimate and one illegitimate – who are almost identical apart from their eyes. When both young men go to war and only one returns alive, having lost both eyes, questions begin to be asked. Is this man who he says he is or could he be pretending to be his brother?

Both of these stories, then, feature mistaken or stolen identities and people who may or may not be impostors and both have enough twists and turns to keep the reader guessing until the truth is revealed. The first one was probably the stronger mystery, but I did enjoy the second one as well and liked the way the story unfolded through letters sent from a sister to her brother. I’m already looking forward to the next Kindaichi book, She Walks at Night, coming next year.

Thanks to Pushkin Vertigo for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.

Book 2 for RIP XX

Book 2 for RIP XX