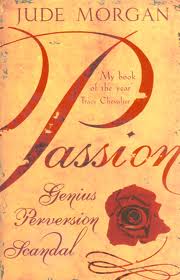

I have read several novels about the Romantic poets and their social circle, including Jude Morgan’s Passion and Guinevere Glasfurd’s The Year Without Summer, but Claire Clairmont has always seemed a shadowy character, who hasn’t come to life as strongly as other women such as Mary Shelley or Lady Caroline Lamb. This new novel by Lesley McDowell changes that by giving Claire a voice and placing her at the forefront of her own story.

I have read several novels about the Romantic poets and their social circle, including Jude Morgan’s Passion and Guinevere Glasfurd’s The Year Without Summer, but Claire Clairmont has always seemed a shadowy character, who hasn’t come to life as strongly as other women such as Mary Shelley or Lady Caroline Lamb. This new novel by Lesley McDowell changes that by giving Claire a voice and placing her at the forefront of her own story.

Clairmont follows Claire throughout three different periods of her life, beginning in 1816 when she accompanies her stepsister Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley) to Geneva. Claire, Mary and Mary’s married lover, Percy Bysshe Shelley, with whom she already has a baby son, are renting a house by the lake, while Shelley’s friend Lord Byron is staying at the nearby Villa Diodati with his doctor, John Polidori. Claire is pregnant with Byron’s child, but it’s becoming clear that he now views her as an inconvenience and would prefer it if the child was never born.

The Geneva episode taking place in 1816, the ‘year without a summer’ which followed a volcanic eruption in Indonesia, is the part of Claire’s life most people will be familiar with (if they’re familiar with her at all). It was during their stay at the Villa Diodati that Mary began to write her famous novel Frankenstein, and it’s through her own relationships with Byron and the Shelleys that Claire has gained historical significance. In addition, this novel also follows Claire during her time working as a governess in Russia in 1825 and later when she settles in Paris in the 1840s, and we gradually begin to see how those events of 1816 have impacted the rest of her life.

There were things that I liked about this book and things that I didn’t (more of the latter than the former, unfortunately). To start with a positive, I appreciated having the opportunity to learn more about Claire Clairmont, having previously known very little about her beyond her involvement with the Romantic poets. I had no idea what she did or where she went later in life, so I found that interesting. The story is not told in chronological order, but moves back and forth in time, with a Russia chapter followed by a Paris one then back to Geneva again, which I thought was quite confusing, particularly as the gaps between the timelines aren’t adequately filled in and no backstory is given for the characters prior to 1816. It felt as though half of the story was missing and it made it difficult to become fully immersed.

The writing is beautiful and dreamlike and at times reminded me of Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet (especially since, like the O’Farrell novel where Shakespeare is never referred to by name, here Byron is always referred to by his nickname, Albe, and never Byron). However, sometimes beautiful writing isn’t enough and I didn’t get on very well with Hamnet so maybe it’s not surprising that I didn’t get on with this book either. The constant jumping around in time and the vagueness of the plot made it hard for me to really get to know Claire and understand her actions. Although I had a lot of sympathy for her because of the terrible way Byron treated her during and after her pregnancy (which has been well documented, including in his own letters), I had no idea what attracted her to him in the first place or how their relationship had reached this point, because none of that is explained or touched upon. Throughout the book, we are continually being dropped into situations that don’t make much sense without being given the full context.

Don’t let me put you off this book if you want to try it – there are plenty of other books I didn’t care for that other people have loved! This will probably be a good read for the right reader; it just wasn’t for me.

Thanks to Headline for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.

Book 7/50 for the Historical Fiction Reading Challenge 2024