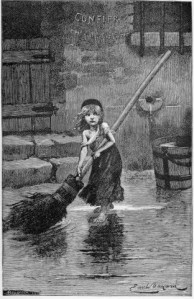

Thérèse is a young woman trapped in an unhappy marriage to her sickly cousin, Camille Raquin. On the surface she appears quiet and passive, never voicing an opinion of her own. But underneath Thérèse is a passionate person who longs to break away from her boring, oppressive existence. When Camille introduces her to an old friend, Laurent, the two begin an affair. Desperate to find a way in which they can be together, Thérèse and Laurent are driven to commit a terrible crime – a crime that will haunt them for the rest of their lives.

Thérèse is a young woman trapped in an unhappy marriage to her sickly cousin, Camille Raquin. On the surface she appears quiet and passive, never voicing an opinion of her own. But underneath Thérèse is a passionate person who longs to break away from her boring, oppressive existence. When Camille introduces her to an old friend, Laurent, the two begin an affair. Desperate to find a way in which they can be together, Thérèse and Laurent are driven to commit a terrible crime – a crime that will haunt them for the rest of their lives.

If you think I’ve given too much away then I can tell you that this crime takes place quite early in the story and is not the climax of the book. The point of the story is what happens afterwards when Zola begins to explore the psychological effects this action has on the characters.

Thérèse Raquin, as you will have guessed, is a very dark book which becomes increasingly feverish and claustrophobic with scenes of violence and cruelty. I haven’t read much 19th century French literature, apart from a few books by Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo, and one thing that struck me about Zola’s writing was how much more daring and graphic this book is than British novels from the same period. The reader becomes locked inside the tormented minds of Thérèse and Laurent, sharing their fear and terror, their nightmares and sleepless nights, their inability to enjoy being together because the horror of what they have done stands between them. If you’ve read Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment or Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart, there are some similarities here.

This book could be enjoyed just for the dramatic plot (it’s as tense and gripping as any modern thriller) but I also thought the four main characters – Thérèse, Laurent, Camille and Madame Raquin – were fascinating and very vividly drawn. Zola apparently said that his aim was to create characters with different temperaments and see how each of them reacted to the situation they were in.

As the first book I’ve read by Zola, I wasn’t sure what I could expect from Thérèse Raquin but I thought it was excellent and I’ll certainly be reading more of his books.