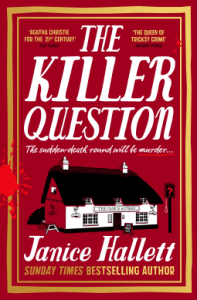

The February theme for this year’s Read Christie challenge is ‘beloved characters’ and Christie’s 1952 novel, Mrs McGinty’s Dead, fits that theme perfectly, featuring not only Hercule Poirot but also another of my favourite recurring characters, Ariadne Oliver!

The February theme for this year’s Read Christie challenge is ‘beloved characters’ and Christie’s 1952 novel, Mrs McGinty’s Dead, fits that theme perfectly, featuring not only Hercule Poirot but also another of my favourite recurring characters, Ariadne Oliver!

The book begins with Poirot being visited by an old friend, Superintendent Spence, who tells him about a crime that has been committed recently in the village of Broadhinny. It involves the murder of an elderly charwoman, Mrs McGinty, found dead in her own home. A small amount of money has been stolen, seemingly providing a motive for the crime. Mrs McGinty’s lodger, James Bentley, who was behind with his rent, has been arrested and found guilty of murder, but Spence isn’t convinced. His intuition tells him that Bentley is innocent, so he asks Poirot to help him find the true culprit before the wrong man is hanged.

In order to find out more about the crime and the people involved, it’s necessary for Poirot to spend some time in Broadhinny, and he finds himself lodging in a guesthouse run by a young couple, Mr and Mrs Summerhayes. This allows Christie to introduce some humour into the book as Poirot finds that, although Maureen Summerhayes is pleasant and friendly, she is also extremely disorganised, forgetful and untidy – the complete opposite of himself! I’m sure Christie must have had fun writing about Poirot’s experiences in the chaotic house – and also the scenes involving Ariadne Oliver, who just happens to be visiting the same village because a local playwright, Robin Upward, is planning to turn one of her novels featuring the detective Sven Hjerson into a play.

Christie’s crime novelist character, Ariadne Oliver, is thought to be based on Agatha herself and provides lots of opportunities for self-parody. I’m sure Christie must have had a certain Belgian detective in mind every time she has Mrs Oliver complain about Sven Hjerson…

“How do I know why I ever thought of the revolting man? I must have been mad! Why a Finn when I know nothing about Finland? Why a vegetarian? Why all the idiotic mannerisms he’s got? These things just happen. You try something — and people seem to like it — and then you go on — and before you know where you are, you’ve got someone like the maddening Sven Hjerson tied to you for life.”

The mystery itself is an interesting one, with Poirot discovering that days before her death Mrs McGinty had been reading a newspaper article about four female criminals and had claimed to know that one of them was now living in Broadhinny. The question is which one – and this forms the basis of Poirot’s investigations for the rest of the book. There are lots of suspects and I thought I’d guessed the correct one, but of course I got it wrong and needed to wait for Poirot to explain it all at the end.

Although this has all the ingredients of a great Christie novel, it hasn’t become a personal favourite – but when an author has written as many books as she has, they’re not all going to be favourites! I did enjoy it and am hoping to join in with some more of the monthly reads for Read Christie throughout 2026.