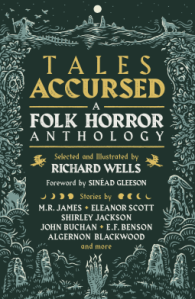

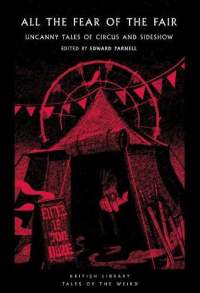

This is the third short story collection I’ve read from the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series and probably my favourite so far. Deadly Dolls was also excellent, but let down by two or three weaker stories, whereas this one is strong throughout, with only one story that I didn’t like very much. As the title suggests, this anthology is themed around fairgrounds, circuses, carnivals and sideshows, all of which provide perfect settings for tales that are creepy, supernatural or in some way ‘weird’.

This is the third short story collection I’ve read from the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series and probably my favourite so far. Deadly Dolls was also excellent, but let down by two or three weaker stories, whereas this one is strong throughout, with only one story that I didn’t like very much. As the title suggests, this anthology is themed around fairgrounds, circuses, carnivals and sideshows, all of which provide perfect settings for tales that are creepy, supernatural or in some way ‘weird’.

There are only a few authors in the book whose work I’m already familiar with. One is Edgar Allan Poe, whose story Hop-Frog opens the collection. I have Poe’s complete works and first read Hop-Frog years ago, but couldn’t remember it very well. It’s about a court jester with dwarfism who takes brutal revenge on the king and ministers who have mocked and taunted him. It doesn’t immediately seem to fit the fair and circus theme, but Parnell includes a short introduction to each story explaining why he chose it and for this one he points out that the character of Hop-Frog is probably the earliest example of the ‘evil clown’ trope in horror fiction.

I think my favourite story was possibly Satan’s Circus by Lady Eleanor Smith, an author completely new to me whose other work now sadly seems to be entirely out of print. Smith was one of the group of 1920s socialites known as the Bright Young Things and claimed to have Romani heritage which inspired her interest in circus life. This story involves a travelling circus which has gained a dubious reputation due to the sinister behaviour of the couple who run it. Another one I enjoyed was The Black Ferris by Ray Bradbury; having read his novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, it was fascinating to see how this story (published fourteen years earlier) introduces some of the ideas Bradbury would later develop in the novel, including a carnival and a ride that goes backwards with startling results!

I also loved Freak Show by Robert Silverberg. The idea of the freak show is obviously very outdated and problematic now, due to the exploitation of the people involved, but this particular story is not at all what you might expect. It features visitors from outer space and makes us question which of us really are the ‘freaks’. I thought it was very cleverly done and I would be happy to try more by Silverberg, an author I hadn’t really considered reading before. Charles Birkin’s The Harlem Horror is on a similar subject and was very well written but reminded me of HG Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau and was a bit too disturbing for me!

Circus Child by Margery Lawrence was another highlight. I’ve never come across Lawrence before, but apparently she wrote several stories featuring paranormal detective Miles Pennoyer and this is one of them. The story follows Pennoyer as he investigates the case of a young woman who has fallen under the spell of a circus hypnotist. One of the creepiest stories in the collection is Waxworks by W. L. George, in which a young couple out walking in the rain take shelter in an abandoned waxworks. I love the atmosphere the author creates in this one. There are also two stories about magicians making people disappear; my favourite was Charles Davy’s The Vanishing Trick, where a man in the audience offers to replace the magician’s assistant – and disappears for real!

Finally, I want to mention The Little Town by JD Beresford (father of Elisabeth Beresford, who created The Wombles). This unusual and eerie story begins with our narrator walking the streets of a small town late at night and finding himself entering a theatre where a puppet show is taking place. The question is – who is pulling the strings? The conclusion to this story has a very obvious interpretation, but when I read Parnell’s introduction I found that the author himself denied that this was what he intended. If any of you have read it, let me know what you think!

The anthology also includes stories by Richard Middleton, LP Hartley, Tod Robbins, Gerald Kersh, Frederick Cowles, Robert Aickman and an author known only as Simplex, who was published anonymously. The most recent story is from 1975, with the majority being from the first half of the 20th century. I couldn’t help noticing that nearly all of the authors featured in this book, apart from Smith and Lawrence, are white men, which surprised me as the other two collections I’ve read in this series have been quite diverse. Still, it was good to have the opportunity to try so many authors who were new to me and to find a few that I would like to explore further.