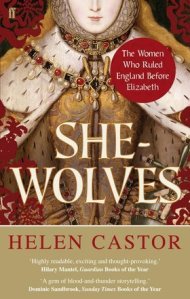

As the title suggests, this is a book about four medieval women who ruled – or attempted to rule – England in the centuries before Elizabeth I.

As the title suggests, this is a book about four medieval women who ruled – or attempted to rule – England in the centuries before Elizabeth I.

* Matilda, daughter and heir of King Henry I, was known as ‘Lady of the English’. She was never actually crowned Queen of England but fought her cousin, Stephen of Blois, for the throne in a period of civil war described as The Anarchy.

* Eleanor of Aquitaine was married to two kings – first Louis VII of France and then Matilda’s son, Henry II of England. Two of her sons – Richard I (the Lionheart) and John – also became King, and Eleanor effectively ruled England as regent while Richard was away fighting in the crusades.

* Isabella, the daughter of King Philip IV of France, came to England as Edward II’s young queen but found that her husband was so obsessed with his favourites (Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser) that he was prepared to put them before not only his wife but also his kingdom. Isabella eventually staged a rebellion with her lover Roger Mortimer and deposed Edward in order to put her young son, the future Edward III, on the throne.

* Margaret of Anjou was Henry VI’s queen consort and played a major part in the Wars of the Roses. With Henry unable to provide the strong leadership the country needed and possibly suffering from an unspecified mental illness, it fell to Margaret to rule in his place and to lead the Lancastrian faction against their Yorkist rivals.

In She-Wolves (the title refers to a term which has been used to describe both Isabella of France and Margaret of Anjou) Helen Castor looks at the lives of each of these queens in turn, before examining their role in history and how they possibly opened the way for Mary I and Elizabeth I to reign in their own right. Unlike Mary and Elizabeth, the four women covered in this book never ruled as sole monarchs but found themselves in a position of power as the daughters, wives or mothers of kings who, for one reason or another, were unable to rule themselves. Henry I died without a male heir and his nephew Stephen was never fully accepted by the English nobility; Richard I spent much of his reign abroad; Edward II lost the support of his barons due to his choice of favourites; and Henry VI was simply incapable of being an effective ruler. In each case, a woman stepped in to fill the gap.

She-Wolves takes us on a fascinating journey through medieval history, but I have to confess that I didn’t read this book in the way it was intended to be read. As I had just finished reading Isabella by Colin Falconer, the queen I was most interested in was Isabella of France, so I read her section of the book first before turning back to the beginning to read the rest. This wasn’t a problem for me as I’m familiar with all four periods of history, but I would still recommend reading the book in order (unless you’re desperate to read about one particular woman, as I was). The final section of the book, which describes the reigns of Mary and Elizabeth, ties everything together and looks at how times had changed enough by the Tudor period for a woman to finally rule alone.

I thought She-Wolves was slightly dry in places but I did find the book well written, interesting and easy to read. Each section starts with a map showing the relevant areas of Britain and Europe and a family tree to help clarify the complex relationships between characters. As this is a work of non-fiction, however, I was surprised by the lack of notes and references – although there is a list of suggestions for further reading at the back of the book and some sources are named directly in the text. These sources include anonymous chronicles such as Vita Edwardi Secundi (Life of Edward II) and the Gesta Stephani (Deeds of King Stephen) and as Helen Castor points out, medieval chroniclers struggled with the idea of women wielding power and tended to focus on the men, which is why we have so little information on the women’s own experiences and actions.

Approaching the end of the book, I was ready to praise Helen Castor for avoiding bias and speculation…until I came across the statement that the Princes in the Tower were ‘murdered by Edward’s youngest brother and most trusted lieutenant, Richard of Gloucester’, stated as fact. It could be true, of course, but I would have preferred an acknowledgment that it might not be and this made me wonder whether the earlier sections of the book had been as unbiased as I’d thought or whether I just didn’t notice as I have less knowledge of those other periods of history.

I don’t think I’m ever going to decide that I prefer non-fiction to fiction, but I did enjoy reading this book and have learned a lot about Matilda, Eleanor, Isabella and Margaret. Can anyone recommend any other good biographies of any or all of these women?