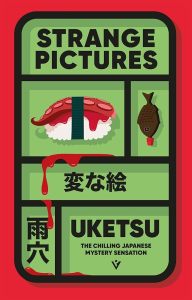

Strange Pictures is a strange novel, but it’s also a completely fascinating one. I’ve been reading a lot of the classic Japanese crime published by Pushkin Vertigo recently, but this is a modern crime novel, first published in Japan in 2022 and made available in an English translation last month. I had never heard of the author, but apparently he’s a ‘YouTube sensation’ known only by the single-word pseudonym Uketsu. He always appears in his videos wearing a mask and his true identity has not been revealed to the public.

In this book, Uketsu takes as his premise the idea that studying drawings made by victims or perpetrators of crime can give us important insights into the psychological state of those people, which could provide clues to help solve the mystery. Strange Pictures consists of three interconnected short stories based around this concept. The links between the stories are not clear at first, but gradually an overall narrative starts to form, raising questions that are answered in a final, fourth section of the book.

Each of the three stories involves some ‘strange pictures’. First, a series of drawings made by a pregnant woman before her death, which her husband posts on his blog. Then, a disturbing picture of a house drawn by a child at school. And finally a sketch of the mountains drawn by a murder victim in the final moments of his life. These pictures are reproduced in the book, along with various other illustrations, and Uketsu interprets them for us step by step as the characters begin to uncover the clues they contain. He discusses the symbolism in some of the pictures and in other cases the physical drawing itself – the paper it was drawn on; the way images can be digitally resized, rotated and layered; the use of gridlines to help with proportion and perspective; coloured crayons that smudge and blur. All of these things and many more are significant to the plot.

The first two stories in the book help to introduce the characters and provide context, but the third one is a great little murder mystery in its own right. I loved the interactive feel, with not just the main drawings but also other sketches, maps and diagrams helping to clarify what’s happening and lead us to the solution. There are also some very creepy moments, particularly a scene with a woman and child convinced they are being followed home to their apartment, and another where a man awakes in his tent in the mountains to discover that he’s no longer alone.

Although I found this book very enjoyable, it’s not one that you would choose to read for the beauty of the prose as the writing style is very plain and simplistic. However, it’s easy to read and while it’s obviously better if you can experience the book in its original language, I think Jim Rion has done a good job with the translation. A second Uketsu book, Strange Houses, revolving around a series of floorplans, is due to be published in English later this year. I’m already looking forward to it!

As Pushkin Press are an independent publisher, I am counting this book towards this year’s #ReadIndies event hosted by Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Lizzy’s Literary Life.

As Pushkin Press are an independent publisher, I am counting this book towards this year’s #ReadIndies event hosted by Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Lizzy’s Literary Life.