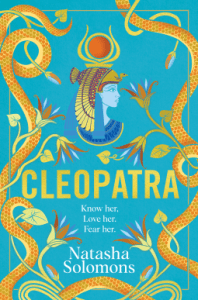

This is a novel about Cleopatra, as you’ll have already guessed from the title and cover! Beginning with a visit to Rome with her father – the first time Cleopatra, then thirteen, has ever left Egypt – and ending just after the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BC, it’s a retelling of the life of one of history’s most famous women.

This is a novel about Cleopatra, as you’ll have already guessed from the title and cover! Beginning with a visit to Rome with her father – the first time Cleopatra, then thirteen, has ever left Egypt – and ending just after the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BC, it’s a retelling of the life of one of history’s most famous women.

Although I love history and historical fiction, Cleopatra is not one of the historical figures I have a particular interest in and I haven’t read a lot of factual information about her. This means I can’t really comment on the accuracy of the book or how the choices Solomons makes on what to cover or not cover compare with choices made by other authors. Purely as a work of fiction, I found it quite enjoyable, especially the parts of the book dealing with Cleopatra’s personal life – her friendship with her beloved servant, Charmian; the development of her relationship with Caesar; and the birth of her son, Caesarion (depicted here as Caesar’s child). Solomons also delves into the politics of the period, the shifting allegiances and power struggles and the changing dynamics between Egypt and Rome. I found some of this a bit difficult to follow and I think including dates at the start of the chapters may have helped me keep track of the passing of time.

The novel is narrated mainly by Cleopatra herself, which allows us a lot of insight into what she is like as a mother, lover, sister and friend. However, there are also some chapters narrated by another woman: Servilia, sister of Cato the Younger and a mistress of Caesar’s (as well as the mother of his eventual assassin, Brutus). There weren’t enough of these chapters for me to fully connect with Servilia on an emotional level, but seeing things from her point of view did provide a very different (and more negative) impression of Cleopatra. I can understand why Solomons chose Servilia, but it would have been interesting if she had also written from other perspectives such as Charmian’s or maybe one of Cleopatra’s brothers and sisters.

The novel ends soon after Caesar’s death, leaving a lot of Cleopatra’s story still untold – her relationship with Mark Antony and the events leading to her suicide, for example. I haven’t seen any indication that there’s going to be a sequel, but there would definitely be enough material for one. Maybe Natasha Solomons will move on to something else for her next book, though; her previous work has included a novel narrated by the Mona Lisa, a reimagining of Romeo and Juliet, and a saga about a wealthy banking family, so clearly she likes to write about a wide range of topics and characters!

Thanks to Manilla Press for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.