It seems to me that most moments in a life can be called interludes: following something, preceding something. Carrying us forward, with our needs and nature and desires, as we move through our time. It also seems to me that it is foolish to try to comprehend all that happens to us, let alone understand the world.

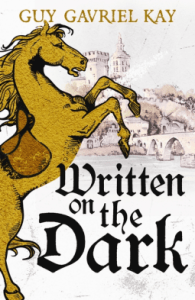

This is a beautiful historical fantasy novel loosely inspired by the life of the poet François Villon. It takes us to a world that will be familiar to Kay readers – a world with two moons, one blue and one white, where the three main religions are Asharite, Jaddite and Kindath, corresponding to Islam, Christianity and Judaism – but where his most recent novels have been set in thinly disguised versions of Venice, Dubrovnik and Constantinople, this one takes place in Ferrieres, based on medieval France.

This is a beautiful historical fantasy novel loosely inspired by the life of the poet François Villon. It takes us to a world that will be familiar to Kay readers – a world with two moons, one blue and one white, where the three main religions are Asharite, Jaddite and Kindath, corresponding to Islam, Christianity and Judaism – but where his most recent novels have been set in thinly disguised versions of Venice, Dubrovnik and Constantinople, this one takes place in Ferrieres, based on medieval France.

On a freezing cold night in the city of Orane, the young poet Thierry Villar steps out of the tavern in which he’s been staying to find that he is surrounded by armed horsemen. He’s convinced that he’s going to be arrested – desperate for money, Thierry had become embroiled in a plot to rob a sanctuary – but to his surprise, he is escorted through the streets to where a man lies dead, brutally stabbed. This is the Duke de Montereau, one of the most powerful noblemen in Ferrieres and the younger brother of King Roch, who is struggling to rule due to mental illness. In return for not arresting Thierry, the provost of Orane asks him to help discover who murdered the Duke by listening to gossip in the city’s shops and taverns.

If you know your French history, you may have guessed that King Roch is based on King Charles VI, nicknamed ‘the Mad’ due to his episodes of mental instability and a belief that he was made of glass. Montereau, then, is a fictional version of the King’s brother, the Duke of Orléans, who was assassinated in 1407. Other people and incidents in the novel can also be connected to real characters and events from the Hundred Years’ War, which adds an extra layer of interest to the story if you’re familiar with this period of history. If not, it doesn’t matter at all since, as all the names have been changed, the book can also be read as a work of pure fiction.

Written on the Dark is a shorter novel than is usual for Kay and feels more tightly plotted than his other recent books, with a stronger focus on the main character and fewer diversions into the stories of minor characters. This probably explains why I thought this book was more enjoyable than the last two or three. Although I know nothing about the real François Villon so can’t say how his story may correspond with Thierry Villar’s, I found Thierry a likeable character; he has his flaws and sometimes makes mistakes, but this just makes him feel more relatable and human. An overarching theme of the book (and of Kay’s work in general) is the idea that even people who are considered ordinary or insignificant can play a key role in important events and influence not only their own fate but the fates of many others.

The fantasy aspect of the novel is limited mainly to the alternate version of France and to a mysterious character known as Gauvard Colle who can communicate with the ‘half-world’. There are also some surprising twists where things like the Battle of Agincourt and the story of Joan of Arc don’t go in quite the direction you would expect! I loved this one and am looking forward to reading his earlier book inspired by medieval France, A Song for Arbonne, which is one of a small number of Kay novels I haven’t read yet.

Thanks to Hodderscape for providing a copy of this book for review via NetGalley.