Earlier this year I read Doomed Romances, a short story collection from the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series. I found it very mixed in quality – some great stories and some much weaker ones – but I was still interested in trying another one and I’m pleased to say that Deadly Dolls is much more consistent. As November is German Literature Month, I had initially planned to read the first story in the collection for now, which happens to be a German translation – ETA Hoffmann’s The Sandman – and leave the rest for later, but I then got tempted by the second story and read the whole book last weekend. The stories are all quite short, which made it a quick book to read!

Earlier this year I read Doomed Romances, a short story collection from the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series. I found it very mixed in quality – some great stories and some much weaker ones – but I was still interested in trying another one and I’m pleased to say that Deadly Dolls is much more consistent. As November is German Literature Month, I had initially planned to read the first story in the collection for now, which happens to be a German translation – ETA Hoffmann’s The Sandman – and leave the rest for later, but I then got tempted by the second story and read the whole book last weekend. The stories are all quite short, which made it a quick book to read!

This selection of fourteen stories is edited by Elizabeth Dearnley and as the title suggests, there’s a shared theme of dolls and toys. The Sandman, published in 1817 – and the story on which the ballet Coppélia was based – is the oldest story in the book, with the others spread throughout the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. It’s a dark story – the Sandman of the title is a mythical character who steals the eyes of human children and takes them back to his nest on the moon to feed to his own children, an image which terrifies our young protagonist Nathanael so much that it haunts him for the rest of his life. I enjoyed it (my only other experience of Hoffmann is the entirely different The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr) but I felt that others in the collection were even better.

A particular favourite was The Dollmaker by Adèle Geras, an author completely new to me. A dollmaker, known to the village children as Auntie Avril, opens a dolls’ hospital, repairing and restoring broken dolls. When three of the children notice that their dolls have been returned to them with alterations that seem unnecessary, they begin to question Auntie Avril’s motives. It seems Geras has been very prolific, writing many books for both children and adults, and I’m surprised I’ve never come across her before. I also enjoyed The Dancing Partner by Jerome K. Jerome (this time an author I know and love), in which a maker of mechanical toys decides to find a solution to the lack of male dance partners reported by his daughter and her friends. Although this is an entertaining story, it does have a moral: that we shouldn’t interfere with nature and try to play God.

At least two of the other stories have a similar message, despite having completely different plots. Brian Aldiss’ fascinating 1969 science fiction story, Supertoys Last All Summer Long, is set in a dystopian future where the rate of childbirth is controlled by the Ministry of Population. Meanwhile, in Ysabelle Cheung’s The Patchwork Dolls, a group of women literally sell their faces to pay the bills. Published in 2022, this is the most recent story in the book and I did find it interesting, if not quite as strong as most of the others. It’s one of only two contributions from the 21st century in this collection – the other is Camilla Grudova’s The Mouse Queen, an odd little tale that I don’t think I really understood and that I don’t feel belonged in this book anyway as it has almost nothing to do with dolls.

Joan Aiken is an author I’ve only relatively recently begun to explore, and as I’ve so far only read her novels it was good to have the opportunity to read one of her short stories. Crespian and Clairan is excellent and another highlight of the collection. The young narrator who, by his own admission, is ‘a very unpleasant boy’, goes to stay with an aunt and uncle for Christmas and becomes jealous when his cousin receives a pair of battery-operated dancing dolls. He comes up with a plan to steal the dolls for himself, but things don’t go quite as he expected! If I’d never read Aiken before, this story would definitely have tempted me to read more! The same can be said for Agatha Christie, whose The Dressmaker’s Doll is another one I loved. This story of a doll that appears to come to life when nobody is watching is maybe not what you would expect from Christie, as it’s not a mystery and there are no detectives in it, but it’s very enjoyable – as well as being very unsettling!

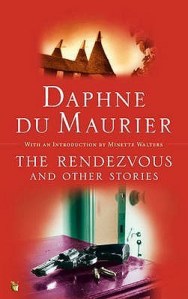

Unlike Doomed Romances, where the stories appeared in chronological order, adding to the unbalanced feel of the book, this one has the stories arranged by subject, which I thought worked much better. For example, two stories which deal with people in love with dolls are paired together – Vernon Lee’s The Doll and Daphne du Maurier’s The Doll. The latter is one I’ve read before (in du Maurier’s The Doll: Short Stories) but I was happy to read it again and be reminded of how good her work was, even so early in her career. There’s also a group of stories featuring dolls’ houses and of these I particularly enjoyed Robert Aickman’s The Inner Room, in which a girl is given a Gothic dolls’ house by her parents and develops an unhealthy fascination with it. In both this story and MR James’ The Haunted Dolls’ House, the houses and their inhabitants seem to take on a life of their own, but in different ways.

I think there are only two stories I haven’t talked about yet, so I’ll give them a quick mention here. They are The Loves of Lady Purple by Angela Carter and The Devil Doll by Frederick E. Smith. I’m not really a big Carter fan, but I’m sure those of you who are will enjoy this story about a puppeteer and his puppet, Lady Purple. I loved The Devil Doll, though. It’s a great story about a ventriloquist whose assistant suffers a terrible fate and is one of the creepier entries in the collection.

This is a wonderful anthology, with only one or two weaker stories, and if you’re interested in trying a book from the Tales of the Weird series I can definitely recommend starting with this one.